We’re used to seeing Toronto as a collection of ethnic neighbourhoods, of parks and trees, and, increasingly, of soaring steel and glass. But U of T English professor George Elliott Clarke wants us to experience a more imaginative and resonant view of the city – what he calls a “transcendent vision” of Toronto.

So last year, Clarke, who will finish his term as Toronto’s Poet Laureate this fall, set to work combing through his vast collection of Canadian poetry to find geographic references to places in the city he calls home. A few months later, he handed over several large envelopes of material to the Toronto Public Library, who matched the poem snippets to their location on a map, and then put the whole thing online.

The result is a city “mapped by emotion,” says Clarke. “It shows us how different parts of the city have had meaningful resonance for poets across decades, and allows us to understand these parts of the city differently.”

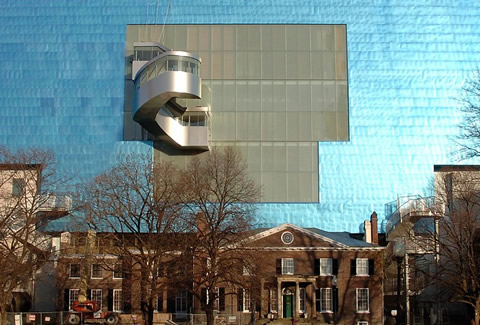

So Grange Park is not just a green block on the map directly south of the Art Gallery of Ontario; it is a place where, as poet Ayesha Chatterjee writes in “(Goldberg) variations,”

On a clear day you can sift titanium

If you step back far enough.

You can watch the sky flex

And flow and petrify

Excerpts from about 200 poems are featured on the Toronto Poetry Map. Downtown locations figure prominently, particularly around Union Station, Chinatown, Yorkville, Little Italy and U of T, but readers are invited to submit suggestions for more.

Clarke says he found the Little Italy poems interesting because many are by first- or second-generation Canadians who explore cultural alienation and the need to connect places in Toronto to a parental or grandparental homeland. “Nostalgia begins to colour the understanding of what Toronto means.”

A poet himself, Clarke says he was struck by how infrequently Canadian poets would mention specific places, until the 1980s – probably because “it was considered less interesting than talking about a street in New York or London.” Raymond Souster, who reached the peak of his success in the 1960s, was the lone exception. “He really deserves to be thought of as Mr. Toronto Poetry,” says Clarke. “He deliberately went against the trend of that time as making us sound blandly American or blandly British.”

Clarke hopes the map will serve to remind readers of the importance of poetry in pinpointing what is spiritually vital in our lives. “It’s possible to look at Toronto and say that it’s a big, business-oriented city, a great multicultural meeting place and so on but after that, what else is it? What is it when we get past the tourist- brochure descriptions of the city?”

As Clarke points out, postcard pictures of Toronto Islands tell one story, this excerpt of a poem by Jacob McArthur Mooney, from his collection Folk, quite another:

Let’s pretend it’s summer, eat ice cream

in the fog. I’ve lost the sense of question

I’ve expected of the city, so let’s go

to where it isn’t and

trace around its shape.

Recent Posts

U of T’s 197th Birthday Quiz

Test your knowledge of all things U of T in honour of the university’s 197th anniversary on March 15!

Are Cold Plunges Good for You?

Research suggests they are, in three ways

Work Has Changed. So Have the Qualities of Good Leadership

Rapid shifts in everything from technology to employee expectations are pressuring leaders to constantly adapt